Back in October 2025, Nick Rochlin, our Science and Data Librarian, sent me a folder of scans of data tables typed in the 1980s. A student had contacted Nick asking if there was an automated way to convert their paper data tables into a format that would allow for computational analysis. There didn’t seem to be a quick solution to offer the student–but there is now thanks to open source AI tools that I’ve been able to adapt for UVic student researcher needs.

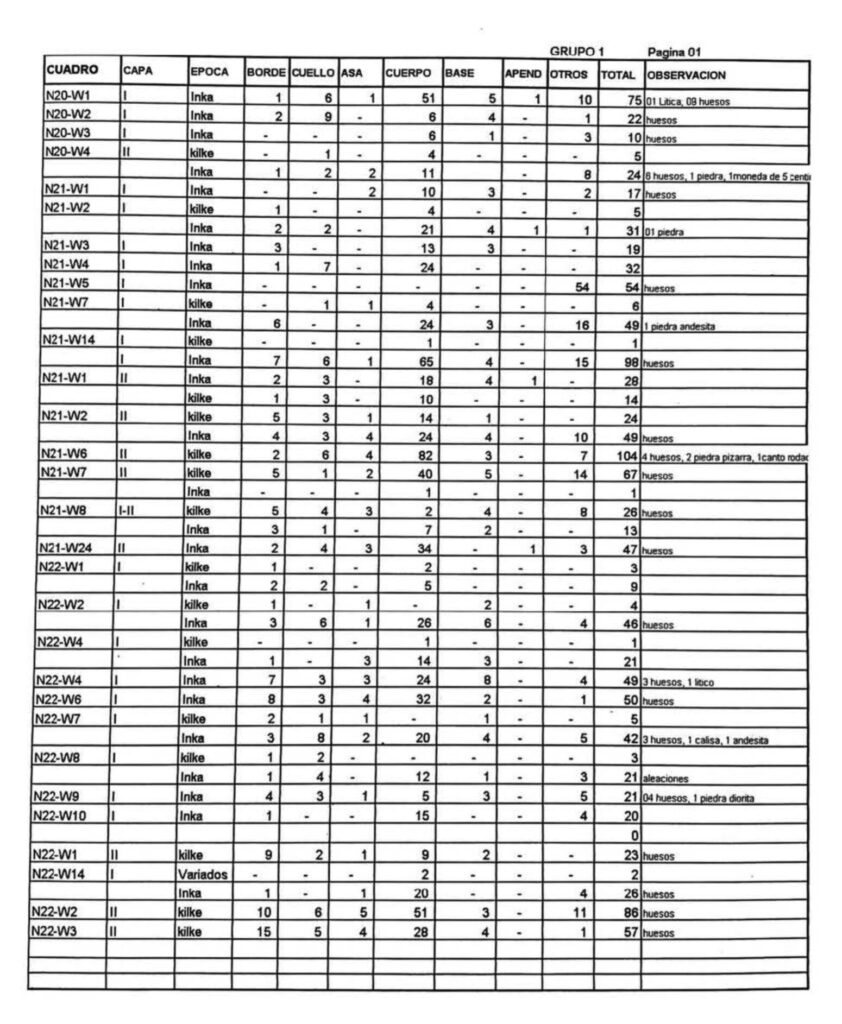

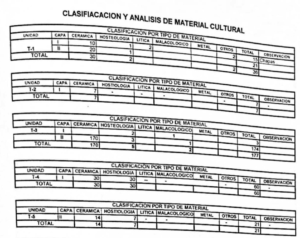

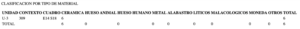

The Problem: Data to be Extracted

The folder contained 323 pages of tables with thousands of rows of archaeological data describing sherds (fragments of ceramics). Each record included Spanish alphanumeric fields, such as where it was found, depth, vessel part, site location, and estimated time period. The student’s goal was simply to avoid manually typing thousands of entries into a spreadsheet over the next three months.

My Initial Approaches

The initial idea I had was straightforward: I could use OCR to convert the scanned tables into CSV files for analysis in tools like Excel or R.

In practice, this approach turned out to be a “worst-case” OCR scenario. The tables were dense with numbers, the layouts were complex, and the scans included issues like page warping and blur. Traditional OCR tools (including Tesseract) struggled to “recognize” the text and early “generative AI” approaches weren’t reliably any better. The most common outputs I achieved were “empty cells,” “misaligned values,” or records split across rows and columns.

Even after I tried other tools (including Adobe Reader OCR, ChatGPT, and hybrid methods), none of the options were reliable enough to scale across the full set of pages. I also tested a few niche, commercial web-hosted tools, none of which were of sufficient quality nor affordable given the high volume of content.

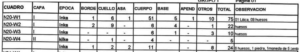

I noticed, however, among those early attempts, ChatGPT 5.1 produced the strongest single result, an example of which is shown below:

Emerging Vision-Large Language Model OCR Tools

Over the last four months, OCR tools based on vision-large language models have advanced rapidly, with multiple new systems appearing in a short time. I had set this problem aside, but recently came across olmOCR2, an open-source vision-language model trained specifically for OCR tasks.

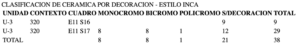

Unlike earlier tools that leaned heavily on linguistic prediction, these newer tools behave more like robust visual recognizers. That matters a lot when the content is mostly numbers and structured tables. Here are two examples of conversions produced by olmOCR-2:

You may notice an apparent discrepancy in the “Cuadro” cell: the scan looks like “E14 518”, while the OCR output reads “E14 S18.” In this case, the correct value is “E14 S18,” which becomes clear when checking subsequent tables.

The “5” versus “S” ambiguity is also a useful example, because it shows the model correctly identifying characters that a human might easily misread when transcribing quickly.

We now had a tool (and surely more to come) at our disposal that can convert these documents into usable data efficiently and accurately, at a reasonable speed and cost.

Why this matters to libraries, archives, and researchers

Tabular data exists everywhere — academic publications, censuses, ledgers, and raw datasets like this ceramics collection. For years, much of it has been “digitized” only in the weakest sense: scanned and viewable, but not usable as data without huge manual effort.

There are vast amounts of tabular data locked on paper in our archives that might not (yet) have a digital life. The more we can unlock this data, the more rich (and accurate) we can make our historical models.

Because the tools I’m using are open source, it is making it easier for folks like me to adapt them to the specific needs of students or organizations. We now have models that can convert scanned tables into usable structured data far more effectively than was realistic even a few months ago.

Additional Tools

Other vision-language OCR tools, including HunyuanOCR and Chandra OCR, are also producing similarly impressive results. They follow the same general direction as olmOCR-2 but differ in training and output formats. Hunyuan can also include coordinates for each element, though the reliability of those coordinates remains to be proven.

Conclusion

The advancements in using vision-language OCR is unlocking data that have long been inaccessible to researchers. By reducing reliance on linguistic prediction and improving recognition of both numeric data and layout, these models are making it far easier to convert scanned tables into common formats like Markdown tables and CSV. Through the Digital Alliance of Canada and Research Computing Services UVic researchers can access the compute needed to do this without having to buy or procure their own GPUs.

The Kula: Library Futures Academy is actively exploring cutting edge technologies that will enable new discoveries across various fields though its Kula Graduate Fellowship Program, which employs computer science students like me. Whether you’re a student, a faculty member, or an independent researcher, we are excited to help you unlock the potential of historical or born-analogue data.